Arch, Cantilever, Column, and Truss

Arch

Arch, a structure composed of wedge-shaped stones, called voussoirs, and designed to span a void. The center stone at the apex or top of an arch is the keystone. It is often emphasized architecturally, but from a structural point of view the keystone is no more essential than any other voussoir. Indeed, in many Gothic arches there is no keystone; two voussoirs simply meet in a joint at the apex of the arch. The two voussoirs that begin the curve at each end of the arch are the springers. They rest on the imposts, the points of apparent support. The impost is generally emphasized by a block of stone that is given special treatment. The undersurface of an arch is called the soffit or intrados; the outer curve is the extrados. The haunch, where the thrust of the arch is usually greatest, is at a point located about one-third the distance between the springer and keystone.

Structural Principle of the Arch. While an arch is being built, formwork or centering is required to support the voussoirs. When the arch is completed, the centering may be removed because the wedge-shaped voussoirs cannot fall without pushing aside their neighbors. In other words, the voussoirs transform the vertical pull of gravity into a diagonal force known as thrust, or lateral thrust. The thrust must be overcome or the arch will collapse. It can be resisted by setting another similar arch against the first so that each presses against the other, as in an arcade. However, an arcade must eventually end, and at that point a buttress or buttressing is needed to give the necessary support to prevent it from collapsing. A buttress is a mass of material heavy enough to absorb, through inertia, the diagonal thrust brought to bear upon it; in effect, it bends the diagonal thrust into a nearly vertical force. The arch is presumed to be safe if the resultant of the diagonal thrust of the arch and the vertical force of gravity of the buttress itself falls within the inner third of the buttress's thickness at ground level.

Everard M. Upjohn, Columbia University

Source: "Arch." Encyclopedia Americana. Grolier Online http://ea.grolier.com/cgi-bin/article?assetid=0019850-00 (accessed August 10, 2007).

Column

Column, in architecture, a vertical support consisting of a base, an approximately cylindrical shaft, and a capital. The term "column" is loosely used in a general sense for any isolated support, such as a post (a slender support without capital or base) or a pier, which may have a rectangular shaft or a cluster of small shafts and may lack a capital.

The earliest columns were simply tree trunks. Later, in ancient civilization columns came to be made of stone. In modern times columns are sometimes wooden copies of stone columns. The shaft of a column is usually composed of drums or cylinders superimposed on one another, although it may be one solid piece. The unit of measurement of the height of a column is the diameter of the shaft at the base; thus, a column may be said to be ten lower diameters high.

The chief purpose of a column is to support a roof beam, entablature, or arch. Most columns are free standing; some, however, are engaged, that is, part of the circumference is embedded in a wall. Occasionally a column may stand alone as a monument, perhaps with a statue on its capital. Examples of monumental columns are the commemorative columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius in Rome and the Monument in London, recalling London's great fire of 1666.

Everard M. Upjohn, Columbia University

Source: "Column." Encyclopedia Americana. Grolier Online http://ea.grolier.com/cgi-bin/article?assetid=0102380-00 (accessed August 10, 2007).

Cantilever

Cantilever, a usually horizontal beam or structure that has a support at only one end; the other end is free. The largest cantilevers are erected by bridge builders. In a cantilever truss bridge, two piers are built in a river, and the cantilevered trusses are extended from each shore over and beyond the piers. A center span is joined to the free ends to complete the bridge.

A cantilever differs from a beam supported at both ends. When a cantilever bends under a load, its upper surface is convex; when a beam supported at each end bends under a load, its upper surface is concave. Frank Lloyd Wright's Robie House (Chicago) and his Falling Water (Bear Run, Pa.) both incorporate cantilevers in their designs.

Albert H. Griswold, New York University

Source: "Cantilever." Encyclopedia Americana. Grolier Online http://ea.grolier.com/cgi-bin/article?assetid=0074730-00 (accessed August 10, 2007).

Truss

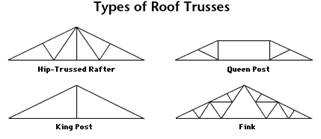

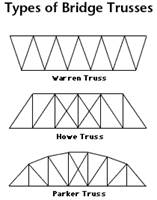

Truss, in architecture and engineering, a timber or metal structural member that is formed of one triangle or a series of triangles in a single plane. A truss requires less material than a solid beam in attaining long spans for carrying heavy loads, making it especially useful in constructing bridges and roofs.

The connected pieces forming the top of a truss are called the upper chord, and those forming the bottom of a truss are called the lower chord. Individual sloping and vertical pieces connecting the chords are called web members, and the whole assembly of these pieces is called the web. At panel points, where the individual pieces intersect, the pieces are connected by bolts, rivets, or welds.

The framing carried by a truss generally is designed so that loads bear on the truss at the intersections of a chord and web member. As a result, the chord and web members are subjected only to tension or compression, and thus less material can be used than what is needed when the truss members also have to resist bending.

Three of the better-known types of trusses¡Xall patented in the 1840s¡Xare the Howe truss, named after the American engineer William Howe; the Pratt truss, named after the American engineer Thomas Pratt; and the Warren truss, named after the British engineer James Warren.

Source: "Truss." Encyclopedia Americana. Grolier Online http://ea.grolier.com/cgi-bin/article?assetid=0393960-00 (accessed August 10, 2007).